Module: Researching Genre

Module Coordinator: Dr Emma Austin

Academic Year 2 (2021/2022)

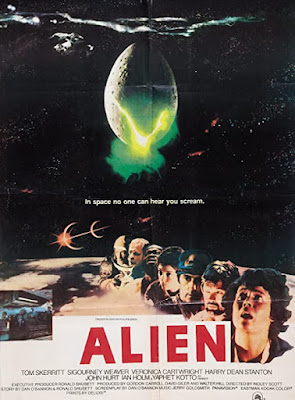

The Horror genre isn’t my favorite, but I do enjoy a rewatch of Alien a couple of times a year. I enjoyed learning and writing about the unheimlich in the context of this horror classic and feel this was the strongest of all my blog-post styled essays.

-

(IMDb, n.d.-a) - This essay will discuss how Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytical theory of The Uncanny (Freud, 2003), or Unheimlich, is represented in Ridley Scott’s film Alien (1979) in relation to the film’s genre: Horror. Freud wrote that the uncanny “belongs to the realm of the frightening, of what evokes fear and dread.” (p. 123)and continues to define Unheimlich as “uncanny” or “eerie”, but “etymologically corresponds to ‘unhomely’” and that “the uncanny is that species of the frightening that goes back to what was once well known and had long been familiar.” (p. 124)

Beginning with the narrative of Alien, we can see there are many familiarities with a typical slasher film, such as Halloween (Carpenter, 1978), which was released the year before Alien. “In narrative terms, it is little more than a science fiction slasher movie, in which an alien creature kills off the crew of a spaceship one by one until it is eventually killed by the film’s own final girl, Ellen Ripley.” (Grainge, Jancovich & Monteith, 2007, p. 439) These facts work in favour of Alien for an audience familiar with Halloween. Bruce Kawin poses a scenario in the introduction of his essay Children of the Light:

Imagine that what is coming at you is a shuffling, gruesome, unstoppable crowd of zombies; imagine that they want to eat you and that they haven’t brushed their teeth since before they died. Did you make up the details of the scene you’re now imagining, or borrow them from memories of George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968)? (Kawin, 2020, p. 360)

An audience’s familiarity with Halloween would enable them to form such connections with Alien, but it may not be a conscious connection, leading to the uncanny familiarity felt when viewing. Scenes may feel familiar, because of the underlying connections in the plot structure, but may also be due to the portrayal of a strong female lead, which wasn’t as common at the time. Brigid Cherry discusses this: “Many respondents felt that the representation of a strong, intelligent and resilient female was a major change from the vast majority of female roles they had previously seen.” (Cherry, 2002, p. 171).

-

(IMDb, n.d.-b)

Alien uses setting cleverly, by lulling the audience into a false sense of security. Scenes change from high contrast and brightly lit areas of the Nostromo to unhygienic, dimly lit, and disorientating service rooms and corridors. Typically, it is the dark and shadowy corners of these rooms where the Alien hunts its prey, with the characters being “safe” in the bright dining area and medical bay. A haunted castle was a frequent element in early gothic, which later became the haunted house. In Alien “The rusting spaceship became the futuristic equivalent of the old dark house full of unseen dangers.” (Bordwell, Thompson & Smith, 2017, p. 335)

Take the scene in which Kane (John Hurt) is exploring the alien spaceship and discovers the room of eggs: There is a pale blue haze at ankle-level, and it isn’t quite clear if it is natural or artificial, but Kane comments that it seems to react when broken. As he kneels to take a closer look, we hear from his perspective an unnerving sound like electrical interference getting louder. This scene is slow and there is a lot for an audience to absorb. This pace is designed to start placing concerns for the crew’s safety into the audience’s minds – it’s the first time in the film where there should really be any doubt of the crew’s safety. The fact that the crew are so far away from, and have lost communication with home/heimlich (the shuttle and by extension, the mothership) and the sense that something terrible is about to happen becomes unbearable, so when Kane slips into the enclosure and nothing terrible does happen, that build-up of tension is falsely released. Very soon after and suddenly, Kane is attacked by the facehugger. Because the tension was already released, this is even more startling for an audience, who have let their guard down too soon. The otherwise slow scene comes to an abrupt end, cutting to an exterior shot of the alien spaceship the moment after the facehugger attacks Kane, robbing the audience of knowing precisely what has happened until Ash (Ian Holm) is examining him in the medical bay later.

The film’s main turning point, of course, is not when Kane is initially attacked by the facehugger, but during the dinner scene. This scene is so expertly crafted to make an audience feel comfortable and safe and is the scene which feels most homely in the entire film – the characters are happy, enjoying a meal around a table, in a brightly lit room. The scene is free from the tension and horror which lead up to it – until it isn’t. The sense of security is shattered when Kane apparently starts to choke on his first bite of food but starts to convulse before the unthinkable: the alien breaks free from his chest, splattering blood over the walls and faces of his mortified colleagues. It is at this point the true feeling of unheimlich is felt, now not knowing if anywhere is safe on the spaceship.

In contrast to the brightly lit scene at the dinner table, the first scene in which we see the Alien in its adult form is devoid of most colour in a poorly lit and closed off section of the ship. It is the complete opposite, in fact: The surfaces are dirty, the water is pouring from the ceiling, and the chains are jangling. This scene is stretched out as much as it can be before it breaks. The persistent sound of the radar device beeping, the chains jangling, and water dripping are unnerving almost to the point of annoyance “evok[ing] fear and dread” (Freud, 2003, p. 123).

-

(IMDb, n.d.-d)

When looking at the characters in Alien there are several links to the Unheimlich. Particularly in the Alien itself and Ash, but also with the character of Mother, the ships artificial intelligence computer. It isn’t until ¾ of the way through the film when we learn that Ash is not human. There have been no indicators before this – he has behaved like a human, even eating and drinking. However, when it is revealed, his behaviour changes significantly. But first, we see a trickle of creamy yellow “blood” – we’re not entirely sure what it is at first but are distracted by Ash’s emotionless expression and sudden superhuman strength. His eyes flicker, as if downloading a command to kill, but that can’t be certain. When he is damaged, he thrashes around like an injured puppy, but it isn’t until his head is torn off when we learn he isn’t human. This scene is perhaps more startling due to how little we really know about the crew. As Morris Dickstein puts well “Alien makes little effort to humanize the crew…” (2004, p. 56).

-

(IMDb, n.d.-e)

The character of Mother, if you consider the ship’s AI computer a character, is a callback to many science fiction films of the 1960’s and 1970’s which used such a character in some form or another. A couple of examples are HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick, 1968) and the Thermostellar Triggering Device in Dark Star (Carpenter, 1974). In Alien the captain of the Nostromo gets their orders from Mother, but it is not entirely clear if Mother is an artificial intelligence, or simply a communication medium between the ship’s captain and the Weyland Corporation. The name “mother” is usually linked with someone who is caring and nurturing and the home. Mother is enclosed in a small spherical room representative of a womb and “we are given a representation of the female genitals and the womb as uncanny – horrific objects of dread and fascination.” (Creed, 2015, p. 57). The links to the unheimlich are when Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) is attempting to communicate with mother and learns of Ash’s ulterior motives in bringing the Alien back to Earth for the Weyland Corporation. Other instances of the representation of the womb are of the alien spaceship and the opening of which the crew use to enter the spaceship, the alien egg Kane disturbs and of course, the Alien creature itself.

When we first see the alien burst from Kane’s chest, it is symbolic of a toothed phallus, but later in the film when it has grown to its adult form, it better represents a succubus-like creature “devoid of any humanity, compassion or emotion [which] amplifies its ability to terrorize the characters and the audience alike.” (Frost, 2011, p. 93) and plays on that fear of the unknown.

We have seen several ways Alien represents the Unheimlich. From the use of setting and visuals, long and drawn-out scenes and sudden false releases of tension, to the unexpected change in a character’s behaviour and representation of the womb. The uncanny is subtle in some areas, but strong in others, but is well represented in Alien.

Citations

- Bordwell, D., Thompson, K., & Smith, J. (2017). Film Art (11th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Carpenter, J. (1974). Dark Star [Film]. Jack H. Harris Enterprises; University of Southern California (USC).

- Carpenter, J. (1978). Halloween [Film]. Compass International Pictures; Falcon International Pictures; Falcon International Productions.

- Cherry, B. (2002). Refusing to refuse to look. Female viewers of the horror film. In M. Jancovich (Ed.), Horror. The Film Reader. (pp. 169–178). Routledge.

- Creed, B. (2015). Horror and the Monstrous-Feminine: An Imaginary Abjection. In B. K. Grant (Ed.), The dread of difference: Gender and the horror film (pp. 37–67). University of Texas Press.

- Dickstein, M. (2004). The Aesthetics of Fright. In B. K. Grant & C. Sharret (Eds.), Planks of Reason. Essays on the horror film. (pp. 50–62). Scarecrow Press.

- Freud, S. (2003). The Uncanny. Penguin Group.

- Frost, C. (2011). Alien. In L. Geraghty (Ed.), Directory of World Cinema. American Hollywood. (pp. 91–93). Intellect Ltd.

- Grainge, P., Jancovich, M., & Monteith, S. (2007). Film Histories. An introduction and reader. Edinburgh University Press.

- IMDb. (n.d.-a). Alien Film Poster. IMDb. Retrieved 2 February 2022, from https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0078748/mediaviewer/rm1173690368/

- IMDb. (n.d.-b). The crew in their hibernation pods. IMDb. Retrieved 2 February 2022, from https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0078748/mediaviewer/rm1173690368/

- IMDb. (n.d.-c). The Alien attacks Lambert. IMDb. Retrieved 2 February 2022, from https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0078748/mediaviewer/rm1514047232/

- IMDb. (n.d.-d). Ash reveals his secrets. IMDb. Retrieved 2 February 2022, from https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0078748/mediaviewer/rm2304547329/

- IMDb. (n.d.-e). Kane’s death. IMDb. Retrieved 2 February 2022, from https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0078748/mediaviewer/rm3407714304/

- Kawin, B. (2020). Children of the Light. In B. K. Grant (Ed.), Film Genre Reader IV (3rd ed., pp. 360–381). University of Texas Press.

- Kubrick, S. (1968). 2001: A Space Odyssey [Film]. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM); Stanley Kubrick Productions.

- Scott, R. (1979). Alien [Film]. Twentieth Century Fox; Brandywine Productions; Scott Free Productions.